Senior Haaretz analyst Amir Oren says that if Obama wins in November, he will likely push for dramatic new reductions in nuclear arsenals; in addition to the U.S. and Russia, Israel may also have to give up some of the nuclear warheads it reportedly holds.

On February 17, Defense Minister Ehud Barak visited the Hiroshima memorial for the victims of the first atomic bomb used on people in human history. Barak, who according to the Japanese news agency Kyodo described the bombing of the city as “one of the unavoidable tragedies” of World War II, viewed the exhibits. His escorts drew his attention to a map of the world listing the number of nuclear warheads in the possession of the atomic powers. There is a number next to Israel’s name, too: “80.” Barak did not respond.

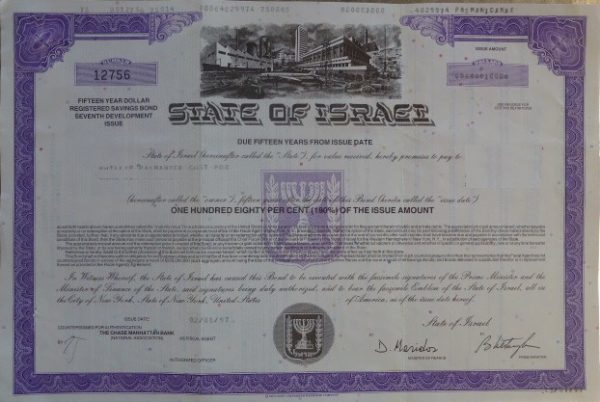

The Dimona reactor - Photo by: Getty images

Israel does not comment on foreign reports about this subject. The data at Hiroshima are based on the conclusions of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Some reports have postulated that Israel has as many as 200 bombs and missiles, but the number usually cited is between 50 and 100.

According to a secret document of the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency, which was drawn up at the end of the Bill Clinton administration and leaked during the period of the George W. Bush administration, Israel had “60 to 80” nuclear warheads in 1999. The document’s authors did not expect this number to change much in the next two decades: In 2020, it was predicted there would be “65 to 85” nuclear weapons in the Israeli arsenal. This was in contrast to the increase DIA expected there to be – mistakenly, it turned out later – in India (50-70 weapons in 2020, as compared to 10-15 at the time ), Pakistan (60-80 in place of 25-35 ) and North Korea (more than 10, as compared with one or two at the end of the 20th century ). The DIA original forecast for Iran and Iraq under Saddam Hussein was identical: Where there had been zero in 1999, each country was expected to have 10 to 20 warheads two decades later.

If in the dozen-plus years since the document was drawn up, the Pentagon has continued to update these data – in accordance with the changing circumstances and the information it has received – this would mean it is conducting continuous surveillance of countries it considers to be nuclear powers. This, of course, would be for operational purposes, such as a strike against North Korea. Knowing the number of targets to be attacked is essential in calculating the number of warplanes (along with fueling, command and control, electronic warfare, pilot rescue and so forth ), submarines and aircraft carriers required in a strike.

Lately, though, there has been another reason for the interest in the number of the warheads: President Barack Obama’s vision to reduce nuclear weapons worldwide. Obama dreamed of such disarmament during his youth, set forth a conceptual framework in his first important speech as president (in April 2009 ), and can be expected to devote a major effort to this subject if reelected in November.

The five declared nuclear powers – the permanent members of the UN Security Council – are partners to the international nuclear nonproliferation regime, but to date the complex strategic-arms limitation and reduction agreements (SALT and two rounds of START ) have obligated only the Americans and the Russians.

Counting missiles and bombs is easy, but it’s difficult to set a numerical value on launchers, bombers and submarines, each of which can have different uses. Even if Britain agrees to be included in the American count, the effort to include also China and France in the agreements – the two refuse to position themselves under an American-Russian umbrella – is doomed to failure.

Obama will therefore try to enlist Russian President Vladimir Putin to exert moral pressure to effect a downward trend. The new version of START, which went into effect last year, will reduce the number of nuclear weapons in the hands of the Americans and Russians to 1,500 warheads and 750 launchers each. That’s still enough to destroy the planet several times over, but far less – only a fifth or even a tenth – than what the two superpowers had at the height of the Cold War.

Veterans’ quartet

These are numbers that the conservatives in American politics – the Republican circles to the right of Obama – can still live with. Not so in the next chapter of nuclear shrinkage. It is being criticized even by those who support the concept – but object to the quantities proposed.

One of them is Henry Kissinger, who turns 89 on May 27, and is clearly a supreme authority in global statesmanship. In the past few years, Kissinger has hooked up with three other veterans among the U.S. foreign and security policy aristocracy: former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, former Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Senator Sam Nunn. These leading figures during the Cold War now advocate elimination of nuclear weapons – “With the proviso,” as Kissinger said last week, “that a series of verifiable intermediate steps that maintain stability precede such an end point and that every stage of the process be fully transparent and verifiable.”

In an op-ed piece in The Washington Post jointly written with retired general Brent Scowcroft, who was his deputy in the National Security Council and his successor as NSC chief, Kissinger expressed concern that the Obama administration is “considering negotiations for a new round of nuclear reductions to bring about ceilings as low as 300 warheads.” That number approaches the ceilings of the other nuclear states.

Kissinger and Scowcroft’s apprehension is based on eight conditions and reservations. “The global nonproliferation regime has been weakened to a point where some of the proliferating countries are reported to have arsenals of more than 100 weapons,” they write. “And these arsenals are growing.” The lower the American ceiling becomes, the more the nuclear order of battle of those countries is liable to constitute a “strategic threat,” especially if they forge alliances and American deterrence fails. The necessary conclusion is that the new nuclear equation must go beyond the Americans and the Russians: Others must do their part as well.

The support of Kissinger, along with Shultz, Perry and Nunn – assuming a rift does not occur between them in the meantime – is essential to Obama.

There can be no more crushing response to the Republicans, who will remain strong in Congress even if its presumptive candidate Mitt Romney loses the election. In seeking to promote his vision of nuclear thinning-out, Obama will turn to the Chinese (240 weapons, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute ), the French (300 ), the Indians (80-100 ), the Pakistanis (90-110 ) and, if the president’s intelligence is accurate and the SIPRI figure at Hiroshima is correct – he will also approach the Israelis.

According to this scenario, a new situation could arise in the relations between Washington and Jerusalem. Since 1968, when the outgoing president, Lyndon B. Johnson, ordered the sale to Israel of Phantom warplanes despite Israel’s refusal to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty – Johnson’s successors, from Nixon to Obama, have accepted Israel’s nuclear policy. The understandings that were reached between Nixon and Prime Minister Golda Meir in 1969 were reconfirmed by Bill Clinton and Netanyahu in 1998, and renewed between Obama and Netanyahu in 2009. These understandings are not binding, however. Israel, which will be viewed as a peace rejectionist or as undermining the world order if it does not discuss disarmament, will discover that there are no “free” arrangements.

A clear hint of this was seen at the NPT Review Conference two years ago in New York, when Obama bowed to Egyptian pressure and agreed to sponsor a regional conference to eliminate weapons of mass destruction in the Mideast – over Israel’s objections. The next such conference is expected to take place in Helsinki either later this year or next year, in any event after the U.S. elections.

If by then Obama will have to deal with an Egyptian president of the likes of Amr Moussa, a declared enemy of Israel’s nuclear project, Jerusalem will be forced to go on the defensive. Everything, including the nuclear issue, will be on the table. The noise Israel is making about the Iranian nuclear project could turn out to be a boomerang that will hurtle toward Dimona.

The entire regional security-political situation – including the Iranian and Israeli nuclear projects, Israel’s ties with its neighbors (e.g., Egypt and Syria ) and talks with the Palestinians – should be one of the focal points of the coming election campaign here. But until now there was only one occasion, in 1965, when the nuclear issue played a part in domestic political wrangling – between Rafi, the party of the nuclear advocates David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Dayan and Shimon Peres, and the newly formed “Alignment” of Mapai, under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir, and Ahdut Ha’avoda, led by Israel Galili and Yigal Allon. The latter two groups were more circumspect on two key questions: budgetary priorities and relations with Washington.

The director general of Israel’s Atomic Energy Commission at the time, Ernst David Bergmann, identified openly with Rafi, which accused Eshkol of some sort of “security failure” – a hint at alleged neglect of the Dimona reactor – and was forced to resign after the 1965 election. At present, thanks to his having been the founding director, Bergmann is the only person mentioned on the commission’s website (Hebrew version ), other than the director general, Dr. Shaul Horev. There is no mention of those who chaired the IAEC between Bergmann and Horev, including Horev’s immediate predecessor, Gideon Frank.

Frank, who headed the IAEC for about 15 years, remained there after retirement in a position that was tailor-made for him: deputy chairman (the chairman is always the prime minister; this is an unnecessary post that threatens to create a barrier between the professional and the political echelons ). Netanyahu, who had Frank as IAEC director general during his first term as prime minister, has wondered aloud whether it might not be right to bring him back. But owing to Frank’s age and the length of his term as director general – well beyond what regulations allow – there was no real chance of this.

Horev, a commodore first class (equivalent to brigadier general ) in the naval reserves, helped transform Israel’s submarines from short-range combat tools into a strategic arm. When he was catapulted to the post of IAEC director general, he was head of the department of special means in the Defense Ministry. It’s likely his successor at special means, Brig. Gen. (res. ) Zeev Snir, will be one of the candidates to head the commission in another year or two, when Horev retires. Another possible candidate is Udi Adam, director of the Nuclear Research Center Negev – namely, the Dimona reactor.

These officials will undoubtedly be part of any consultations that take place concerning the regional implications of the world trend vis-a-vis nuclear weapons. But supreme authority devolves on the top political echelon in Israel: not the defense minister or the prime minister’s deputies, but the prime minister himself. That’s one more reason for Israel’s citizens to examine carefully the judgment, good faith and the purity of motives of the candidates for the position.

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate