40 years on, the Yom Kippur War cost 2,522 Israeli fatalities, traumatized a generation & profoundly impacted the Jewish state.

By AMOTZ ASA-EL

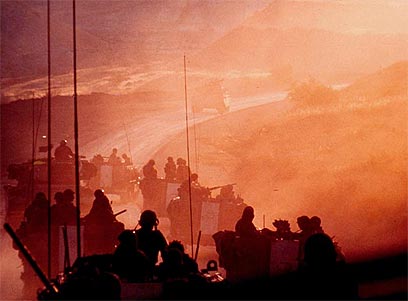

IDF TROOPS cross the Suez Canal, October 1973. – Photo: Jerusalem Post archives

By day’s end, with nearly half of the soldiers in those outposts dead, vast Egyptian armies parked at Sinai, and 1,400 Syrian tanks on the Golan Heights – one fact hovered above the battlefield’s thick fog: Israel had been stunned.

Forty years on, the war that cost 2,522 Israeli fatalities, traumatized a generation and profoundly impacted the Jewish state’s society, politics, economy and psyche, refuses to go away.

The warriors, now mostly grandfathers, are writing memoirs, holding spontaneous reunions and retrieving diaries, photographs, recordings and even rare footage taken with the era’s bulky 8- mm. Kodaks, in what adds up to a collective quest for closure.

The rest of Israel, surveying where it has since journeyed, has reason to proverbially enter these makeshift group therapies, place a hand on the shoulder of each of the Yom Kippur War’s veterans, look them in their wrinkling faces, and quietly tell them Jeremiah’s consolation to Rachel: “There is a reward for your labor.”

STRATEGICALLY, the war will be counted among military history’s grand surprises, alongside Pearl Harbor and Operation Barbarossa.

Israel was caught off-guard in almost every respect. It underestimated the enemy’s intentions, abilities, weaponry and motivation. The leaders misinterpreted Egyptian president Anwar Sadat as a babbler, the generals did not enlist the reserves, the pilots were humbled by the radar-guided SA missile and the tankists by the shoulder-carried Sagger.

Then again, not only did the IDF ultimately prevail, in 40 years’ hindsight it emerged from the war with long-term strategic gains that dwarf the its immediate setbacks.

Tactically, the war’s tide was turned on both fronts: on the Golan Heights, the vastly outnum-bered Seventh Brigade managed to fend off the Syrian armored thrust, and thus open the IDF’s path to Damascus; and in Sinai, the Egyptian Third Army was encircled and the Suez Canal was crossed as the IDF reached within an hour’s ride from Cairo. Yet what at the time seemed like heroism that merely decided one war, actually went much farther.

First, the recollection of prevailing even under such duress, and of successful improvisations along the entire hierarchy – from foot soldier to general – helped foster a culture of inventiveness from which Israel benefitted in other tests. But far more important, following the Armageddon that included some of history’s largest armored battles, Israel’s enemies never again unleashed on it a conventional army.

The realization that Israel prevailed even in a war waged, from the Arab viewpoint, under ideal conditions, convinced Arab leaders to abandon traditional war, and opt for assorted alternatives – from guerrilla and terror wars to peace deals. While far from reflecting a pro-Zionist conversion, the Arab abandonment of the traditional military option is a major strategic gain for Israel, and a direct result of the Yom Kippur War.

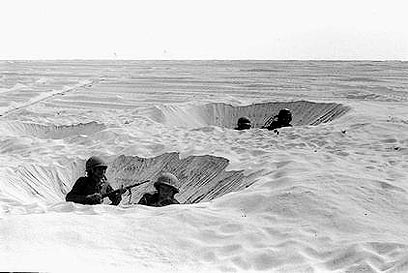

WHEN THE fighting ended, it turned out that one outpost of those that initially confronted the Egyptian onslaught, the northernmost, endured the entire war. Having emerged from it intact and returned home bewildered, Capt. Motti Ashkenazi went to Jerusalem, stood outside prime minister Golda Meir’s office and demanded that she and her cabinet resign.

Ashkenazi was soon joined by thousands who felt a deep sense of disillusionment and were now spontaneously forming Israel’s first effective protest movement. By the time Golda Meir resigned the following year, it was clear that the repercussions of the Jewish state’s Pearl Harbor would exceed the narrow realms of warfare, and include Israel’s politics, society and state of mind.

Politically, the future was hinted at in the first postwar election, when the newly established Likud won more of the soldiers’ votes than Labor.

In the following election Labor lost power for the first time, and its political hegemony for good.

The establishment’s subsequent transition from secular socialists to traditionalists and capitalists; the disappearance of the European-born generation that led Israel in its first three decades; and the passage of the settlement ideal from the kibbutzim’s liberal farmers to the West Bank’s messianic rabbis, make the Yom Kippur War a watershed in practically all aspects of Israeli history.

Back in autumn ’73, all protagonists of this gathering transformation shared a sense of crisis and agony, some because they felt they were losing their grip on Israeli society, and some because they could hardly wait to seize it.

Gradually, the Yom Kippur War came to be seen as an engine of a great schism.

It wasn’t.

THE MOST notable realm where Israeli pragmatism and resilience prevailed is the economy.

Back when the war ended, Israel was financially strapped.

The knowledge that it was won thanks to emergency arms shipments from America; the consequent dependency on American aid; the inflation that began that year and soon spun out of control; and envy of Arab oil wealth which those days cast a shadow over the global economy – all generated an economic pessimism that complemented the overall atmosphere of cynicism and despair.

Golda Meir, Ariel Sharon in Sinai during war – Photo: יהודה ציון, לע”מ

Forty years on, Israel’s is among the world’s strongest currencies, its growth rate is among the world’s highest, its unemployment, inflation and interest rates are among the world’s lowest, and its innovations are the toast of investors from Tokyo to New York. On top of that, for more than 15 years, Israel has no longer been accepting US civilian aid. These accomplishments belong collectively to Israelis of all persuasions and backgrounds, who meet daily in workplaces where they do together what a seriously divided society could never create.

The same can be said of Israeli culture, which over the past 40 years has seen the previously unthinkable rise of religious authors and filmmakers, symbolized by novelist Haim Sabato, a rabbi and rosh yeshiva who emerged from the war a prize-winning novelist.

In fact, the cultural traffic ignited by the war proved to a two-way street.

Yom Kippur War (Archives) – Photo: לע”מ

The sense of perplexity, enhanced by David Ben-Gurion’s death five weeks after the cease-fire, was expressed by the era’s popular songs, three of which became timeless, and inspire a melancholy that moves Israeli hearts to this day.

One, penned by songwriter Haim Hefer, a veteran of the War of Independence who wrote some of its most popular hits, now had an unnamed soldier promise his little girl – “in the name of the pilots who thrust into angry battle,” and the gunners “who were the pillars of fire along the front,” and “all the fathers who went to battle and never returned” – that 1973’s would be the last war.

A second song, by “Jerusalem of Gold” writer Naomi Shemer, placed “a white sail in the horizon, opposite a heavy black cloud,” and “holiday’s candles shimmering in dusk’s windows,” while asking “What is the sound of war I am hearing, the sound of shofar and drums,” and then praying, “If the announcer stands at the door, place a good word in his mouth, if only all we ask – would be.”

The whisper of prayer that both songs shared was the zeitgeist, so much so that it even arrived in Kibbutz Beit Hashita – whose veterans included diehard Marxists and atheists.

Yom Kippur War – Photo: David Robinger

Tucked in the Jezreel Valley north of Mount Gilboa, where the biblical Saul and Jonathan died in battle, this community lost 11 of its sons in the war.

Having lived in their midst at the time of their grief, composer Yair Rosenblum wrote a tune for U’Netane Tokef, the prayer which states that on Rosh Hashana God drafts, and on Yon Kippur he seals, the verdict of every man: “Who will live and who will die, who is in his end and who is not, who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast, who by hunger and who by thirst.”

The tune brought together Zionism’s epitomes of the New Jew, the atheist warriors of the kibbutzim, with Rabbi Amnon of Mainz, the prayer’s writer and the ultimate Old Jew, a sage whom legend says was killed without a fight after refusing a demand to convert.

Animating the most solemn moments in Judaism’s holiest days, the tune has since come to be sung annually in thousands of synagogues throughout Israel, and has even been performed by some ultra- Orthodox singers and cantors.

Yom Kippur War (Archives) In the Sinai – Photo: לע”מ

THE YOM KIPPUR WAR, then, had more effects on Israeli society besides political divisions, and the most decisive of these was humility. The arrogance and swagger that followed the Six Day War were initially followed by anger and acrimony, but what for a moment seemed like despair soon gave way to a sense of appeasement and constructive soul searching. This humility is particularly evident where it is needed most, namely in the way Israeli generals speak and think.

Forty years on, it is clear that Israeli society was not debilitated by the Yom Kippur War and in fact, soon resumed its development in earnest.

Having left us while the war’s trauma was fresh, one feels like updating Ben-Gurion that since his departure: no Arab army again waged war on Israel; there are two peace agreements; the population has more than doubled and the economy more than quadrupled; there are more Jews here than in any other country; the number of Israeli Jews has just crossed, for the first time, the charged figure of 6 million, Soviet Jewry is here, and the Soviet Union is gone; and Israeli society, while varied and complex, remains intact even when the rest of the region is ablaze with civil wars – and that U’Netane Tokef, as written in medieval Germany and composed in Kibbutz Beit- Hashita, will tomorrow echo from Metulla to Eilat.

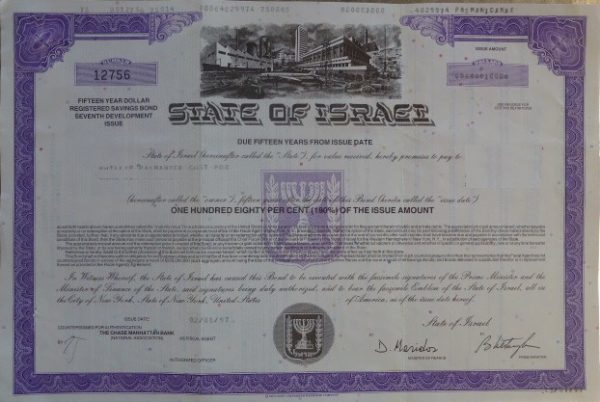

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate