Israel’s choice may be between selling gas quickly that may anger the Russians, or looking at a more long-term prospect without alienating the U.S.

Last month, the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced plans to export up to 40 percent of the gas from Israel’s Eastern Mediterranean fields, with expected earnings of up to $60 billion over a 20-year period. This is, however, only the first step toward realizing export revenues from Israel’s gas reserves, a process fraught with complicated choices over the route and destination of those exports. Rather than aiming to use its gas for any great geopolitical gains, Israel currently seems happy to avoid unsettling interested parties while it reaps long-term economic gains from its gas bounty.

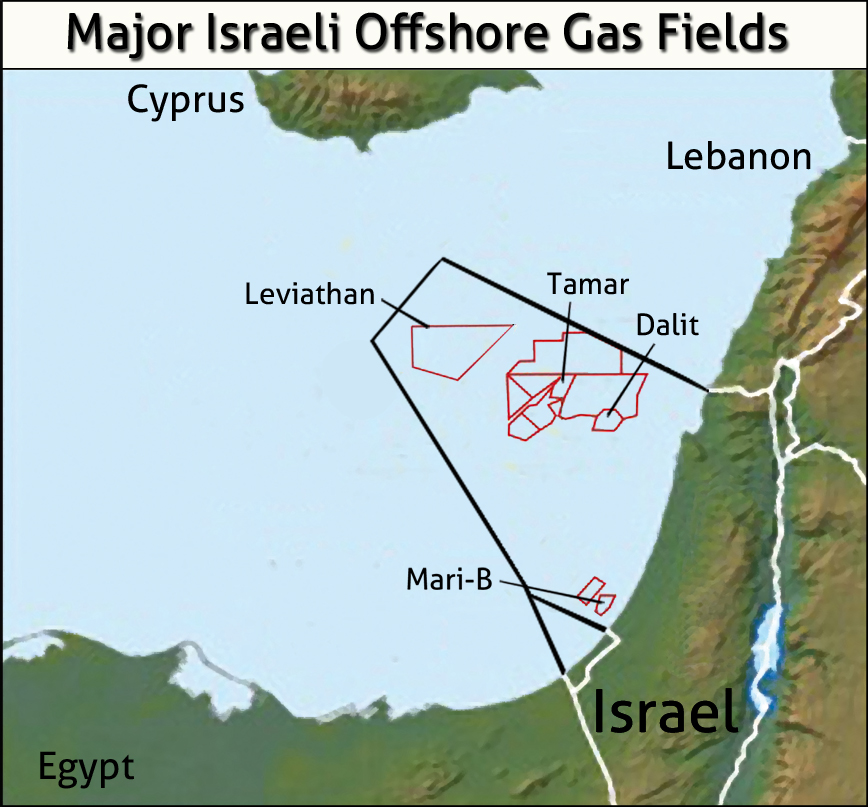

Tamar offshore gas field – Photo: Albatross

Domestically sourced gas has come as a great relief for Israel, which had been reeling under high electricity prices since the cutoff of Egyptian gas supplies following pipeline attacks in the Sinai in 2011 led to gas-based electricity generation being substituted with expensive oil-fired generation. The memory of these recent hardships has made public opinion in Israel averse to the idea of sending gas abroad, and protests against exports were a key reason for the delay in approving them.

But export Israel must, if only to keep existing investors happy and attract new ones. The current consortium developing Israel’s two largest fields, Tamar and Leviathan, led by Texas-based Noble and Israel’s Dalek, has made it clear it needs clarity on exports before it will conduct further prospecting. The 40-percent export quota, however, was reduced from the 53 percent earlier proposed by the Tzemach committee, which was created to draft Israel’s national energy policy, limiting the options available to the companies involved for selling gas from Israel’s current proven reserves.

The easiest option to realize quickly is probably to export gas to Turkey via pipeline. This route would have the support of the United States, which has urged Israel to export gas to its neighborhood, especially Jordan and Palestine. Jordan, which has also suffered greatly from the near-drought in Egyptian supplies, is already in talks with Israel for gas imports. Cheap and potentially carbon-competitive gas-based electricity would foster development in both Palestine and refugee-ridden Jordan and thereby potentially reduce regional instability.

On their own, however, Jordan and Palestine do not constitute viable regional markets that would justify large-scale investment in pipelines. Only the inclusion of Turkey does. Israeli supplies to Turkey could reduce the latter’s dependence on Russia and Iran, which would give Ankara a freer hand on issues such as the conflict in Syria. But the fact that an Israeli gas pipeline to Turkey could also connect on to Europe is bound to arouse Russian suspicion.

Moreover, the pipeline route to Turkey with the shortest payback period traverses the waters of Lebanon and Syria, both countries that are hostile to Israel’s energy aspirations. Hezbollah has already vowed to back Lebanon’s dispute with Israel over the Leviathan gas field and has been bolstering its inventory of anti-ship missiles. Alternative deep-sea pipelines are not currently viable given the expected earnings.

In any case, the potential net earnings from a Turkey-bound pipeline pale in comparison to those that could be realized through tapping high-value liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets in Asia. Regional gas supply prices are not high enough to attract players with the heft and expertise to further tap Israel’s share of the Levantine basin, which is needed for Israel’s offshore holdings to reach their true potential of anywhere between three and five times Israel’s current proven reserves. And these players would naturally have a greater say in the commercial direction of their prospects.

The LNG route would increase Israel’s flexibility considerably and make it a longer-term player in the energy market. However, the process of building an LNG export terminal, in addition to being lengthy, comes with its own set of issues. First, securing environmental clearances for an LNG terminal on Israel’s crowded Mediterranean coastline is far from guaranteed. Second, given that this option does not preclude exports to Europe, it is also bound to be watched closely by Moscow. Indeed the Russians are so keen to have a say on which way the gas heads that they have expressed interest in financing floating LNG terminals over the Leviathan and Tamar fields.

Besides building its own terminal on its Mediterranean coast, Israel could also join Cyprus in building one. The consortium led by Noble signed a preliminary agreement with the Cypriot government for an LNG export terminal that would be linked to Cyprus’ own offshore gas fields. But using Cyprus as a conduit for LNG supplies would mean accommodating Turkey, which continues to refuse to recognize the Republic of Cyprus. And despite recent improvements in Israel-Turkey relations, the price of accommodating Turkey may not be worth the effort.

Finally, supplying LNG to Asia, which would be far more lucrative than supplying the European market, would require traversing the Suez Canal. Given the volatility uncertainty of Egypt’s domestic political situation, that is not an attractive option for Israeli policymakers. This is why the feasibility of an LNG station in Eilat on the Red Sea coast, connected via an overland pipeline with Israel’s offshore finds, is also being studied. An LNG export terminal in Eilat could attract the interest of hydrocarbon majors in India and China, who could also help Israel with city gas distribution projects—an area where Israel has no expertise.

This option would demonstrate that Israeli gas exports are firmly targeted at Asian markets and not intended to tread on Russia’s European toes. Moreover, Eilat could easily serve as a hub for serving Jordan and Palestine via pipeline, thereby taking care of the immediate neighborhood. The Gulf Cooperation Council states, and even Washington, however, will watch the impact on supply prices very carefully. Israel’s choice therefore is between selling gas quickly and angering the Russians, or looking at more long-term prospects while trying not to alienate the U.S. Either way, it may find that finding gas was the easy part.

View original World Politics Review publication at: http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/13086/flush-with-gas-israel-now-must-find-ways-to-export-it

About the Author:

Saurav Jha studied economics at Presidency College, Calcutta, and Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He writes and researches on global energy issues and clean energy development in Asia. His first book for Harper Collins India, “The Upside Down Book of Nuclear Power,” was published in January 2010. He also works as an independent consultant in the energy sector in India. He can be reached at sjha1618@gmail.com.

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate