As foreign companies are acquiring the ‘Start-up Nation’s high-profile companies that were providing hundreds of jobs locally, Israel’s market is being brain-drained as they move abroad.

By Reuters

Israeli entrepreneur Avi Brenmiller says he was coaxed by investors into selling Solel, his solar-thermal power firm, to Germany’s Siemens for $418 million in 2009. Today, little is left of it after Siemens pulled out of the business.

From a thriving company that employed over 500 people, Solel has been reduced to a factory with 50 workers. Brenmiller’s experience is one of a growing number of cases illustrating the double-edged nature of Israel’s high-tech boom.

While many entrepreneurs and investors have made lots of money from Israel’s start-ups over the past two decades, increasingly firms acquired by foreign buyers are then either shut down, with their intellectual property moving abroad, or turned into R&D centers for the parent company.

Israel’s high tech industry is a major growth engine and investment magnet, attracting multinationals like Apple, Intel and Google, who have been eager to snap up local start-ups.

High-tech goods and services account for 12.5 percent of Israel’s gross domestic product (GDP) and half of its industrial exports, government data shows. Israel leads the OECD when it comes to R&D, spending 4.3 percent of GDP on it, nearly twice the OECD average, according to Ernst & Young.

Companies often tap into the skills of workers trained in the military or intelligence sectors and start-ups benefit from tax breaks and government funding. But Karin Mayer Rubinstein, head of the Israel Advanced Technology Industry association, said that while M&A brought money into Israel, patents were being “vacuumed” out.

“In the last few years, most of the companies being bought don’t stay here as a separate entity,” she said.

Jobs warning

Many Israeli companies are not growing into global players that acquire others rather than being acquired. This trend is creating an economic problem, said tech pioneer Dov Moran, who sold his firm M-Systems – which developed the USB flash drive – to SanDisk for $1.6 billion.

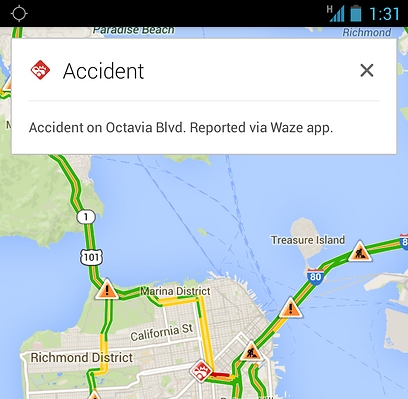

He said some companies should be sold because they would not be successful on their own. He pointed to Google’s $1 billion acquisition of mapping start-up Waze as one such case.

“But the fact that companies are sold is not really great for the country. Only R&D is kept in Israel, not sales, not logistics,” Moran said. “We need companies that are creating jobs not just for talented engineers and programmers.”

After job creation in the high-tech sector grew an average of 2.5 percent annually from 2004-2012, it has started to shrink, contracting nearly 2 percent in total in the past two years, government figures show, even as the overall jobless rate fell.

Looking back, Moran said that had he stayed the course, M-Systems could have grown to a company with $3-$4 billion a year in sales. Today it operates as a SanDisk R&D centre and its workforce has fallen to 700 from 1,000 before the sale in 2006.

There are 282 R&D centers in Israel, most owned by foreign firms. Eight out of 10 Israeli technology firms bought by multinationals become a foreign R&D centre in Israel, or are integrated in existing foreign R&D centers, said the Israel Venture Capital (IVC) Research Center.

Entrepreneurs say investors are often looking for high returns as quickly as possible. “To build a long-term success story takes hard work, many years and lots of patience,” Brenmiller said.

Patience is not a strong point in Israel’s start-up culture, where entrepreneurs like to move from one idea to the next.

Israeli venture capital-backed companies take an average of 3.95 years from the first round of funding to acquisition, compared with 6.41 years in Britain and 6.66 in France, according to third-quarter 2014 figures from Dow Jones VentureSource.

Signs of Maturity

Solel is not alone in its experience. Chromatis Networks was one of the biggest acquisitions ever of an Israeli company when it was bought by Lucent in 2000, but was shut down about a year later. IBM closed XIV in 2008 about a year after it paid $300 million for the storage technology firm, according to IVC.

Waze after it was acquired by Google

But there are some signs the sector is starting to mature as more companies are willing to wait longer before selling, aiming to build themselves up to a stand-alone size.

In 2014 there were 70 Israeli “exits” – stake sales from mergers, acquisitions or initial public offerings (IPOs) – valued at nearly $15 billion, according to PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC). But of that, $9.8 billion was in IPOs – up from $1.2 billion in 2013 – while the value of M&A fell to $5 billion from $6.5 billion.

This can partly be attributed to the fact many successful entrepreneurs are on their second or third company, said Rubi Suliman, head of high-tech at PwC Israel.

Brenmiller is one such case. He poured $20 million from the sale of Solel into establishing Brenmiller Energy, which has developed a more efficient way to store heat from the sun.

To keep more companies, the Israeli government needs a long-term plan for incentives and support rather than simply early-stage aid, Rubinstein said.

With wealthier entrepreneurs and less pressure to sell, some believe Israel could begin producing more large companies such as network security provider Check Point Software.

“It is very understandable that a second-time entrepreneur with a large bank account is much more patient in his next venture and much more willing to take risks,” said Suliman.

View original Ynet publication at: http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4616971,00.html

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate

Israeli New Shekel Exchange Rate